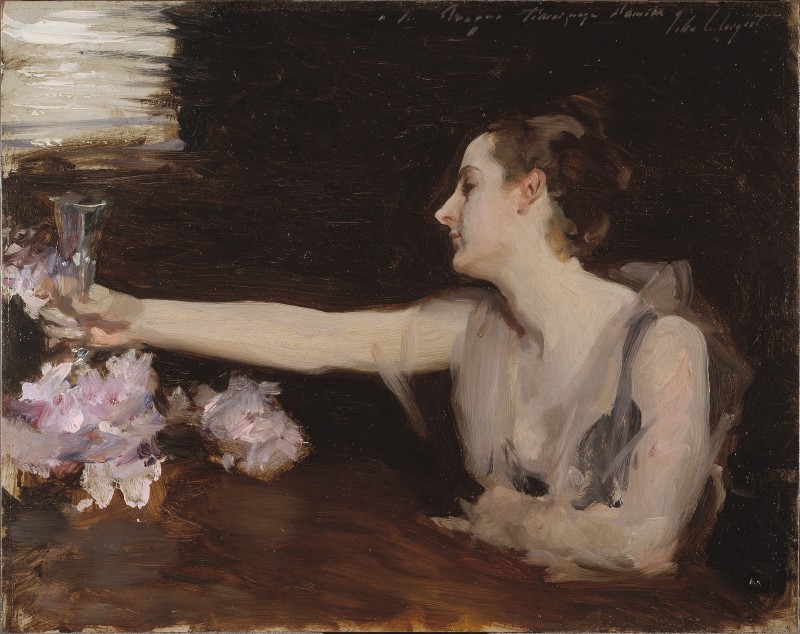

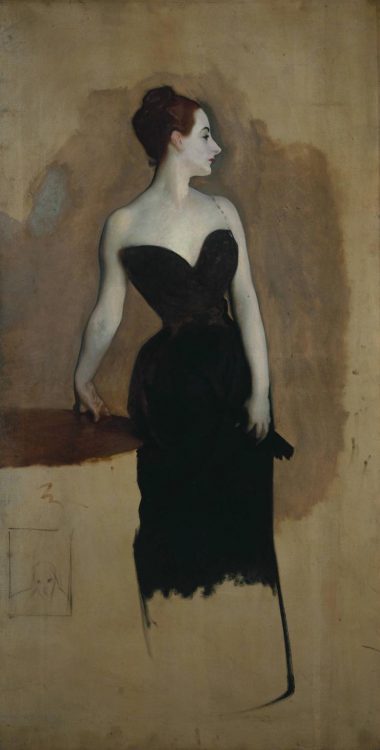

The first time I saw John Singer Sargent’s Madame X I didn’t get it. I thought, what a boring painting to have caused a scandal. Recently, I ran into an image of the painting on a book cover. At the time, I was perusing the library for material on the use of the profile in Florentine portrait art. Staring down at Madame X with her face turned away in profile I murmured, “genius.”

(Two people turned to stare.)

A Profile Portrait of Madame Gautrau

The portrait depicting the Parisian socialite, Madame Gautreau, was originally debuted at the 1884 Paris Salon, instantly sparking scandal. The work’s controversy can be understood by examining Gautreau’s contrapposto pose which presents herself as both a Lady and an odalisque. As the art critic Susan Sidlauskas writes, “Gautreau’s tensed body challenged the entire cultural history of how a woman should pose.”

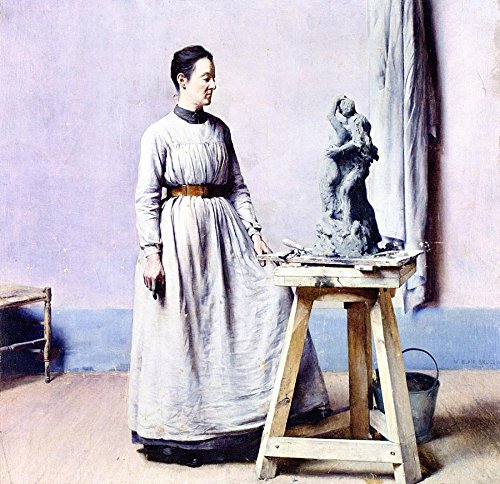

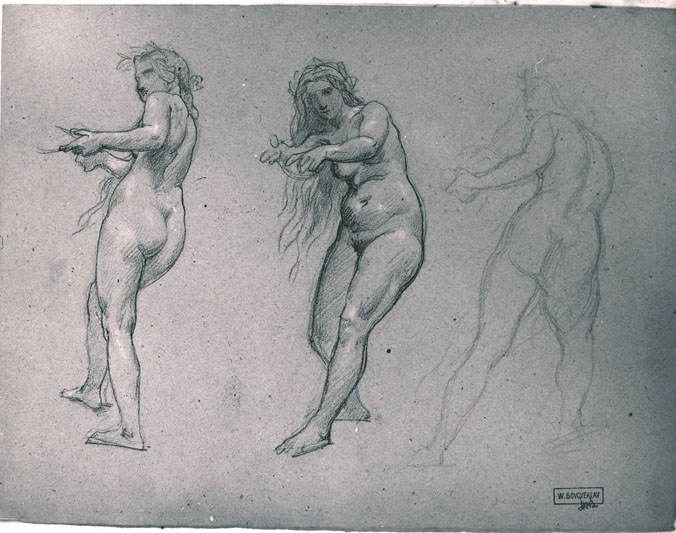

In profile, Gautreau asserts her virtue and social standing. The significance of the profile dates back to the Renaissance, first popularized in the portrayal of Florentine Noble women. Pictorially, the profile was used to keep a safe distance between a Lady and her viewer. Because she looks away the viewer assumes she is unaware of its gaze (and presumably her own beauty), therefore preserving a sense of the sitter’s modesty and humility. Over time the profile entered the lexicon of painting and came to signify a woman’s virtue and social status as a Lady.

Although her head is in profile, Gautreau seems to twist her torso into a frontal position offering a full view of her body. The pose suggests that while she plays the part of a Lady, Gautreau is active in the seduction of her audience.

What’s not properly understood in our contemporary age is that female nudity portrayed in classical art was considered different to actual female nakedness. It was seen as improper to portray the naked body of a real woman. By in large, nudes were of mythical subjects and it was understood that the artist was not working from a live model but an interpretation of classic Greek sculpture. These depictions were rationalized as a philosophic expression of beauty through the depiction of geometric harmony of the human form.

Actual women were still portrayed much like they were during the Renaissance – showcasing their virtue and humility.

So Sargent’s depiction of a real woman, of high standing no less, actively presenting herself to be admired was in fact very radical for its time.

To underscore the subject’s agency she wears a pendant with the symbol of the Roman goddess of hunt Diana. In the original version, the strap pinned to the dress by the pendant of the huntress falls from her shoulder. The implication of the fallen strap was so damning that Sargent eventually repainted that portion of the work showing the strap in place on her shoulder.

Sargent’s Painting Interrogates Beauty

Examining Sargent’s painting, we see it is not a portrait of a real person but a meditation on the nature of beauty. Sidlauskas writes, “when [Sargent] defended himself against his severest critics, he invoked the fidelity of his canvas to his sitter’s public persona.”

Gautreau, was an outsider to French society who infiltrated this exclusive world using her looks and a carefully curated public persona. In her time, she was considered the most beautiful and fashionable woman of Paris. She was famous and became a sort of symbol of beauty in French society.

More than challenging the Lady’s reputation, Sargent is using her image to challenge the culture’s popular understanding of beauty.

In portrait art beauty came to signify the goodness of the sitter. It was believed that beauty was an innate quality and the viewer believed that by evaluating the physical beauty of a subject they could know something about the person’s character.

In his painting Sargent portrays beauty not as an innate quality but as a kind of persona. For Sargent, beauty is an act. By presenting herself in an extreme contrapposto – a pose associated with Venus herself – Gautreau is playing the part of the beauty.

This wonderfully exaggerated twist that defines the subject’s pose shows her simultaneously twisting her body into view and diverting her gaze away from the viewer. With her head in profile the beautiful Gautreau is refusing to be known and Sargent refutes the notion that beauty is a window into the sitter’s soul – or the visual embodiment of goodness.

Sargent’s Idea of beauty

To fully understand Sargent’s idea of beauty, consider the next painting he did after the Madame X affaire. So violent was the reaction to his portrait of Gautreau that Sargent left France and sought refuge in England.

Living in the countryside with friends, Sargent took almost a year to produce his next work, Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose. Like so much of Sargent’s art it would be easy to write this painting off as sentimental arrangement of children and flowers. But like his portrait of Gautreau, Sargent is not focused on his subject but what gives it life.

The painting shows two little girls lighting lanterns at dusk. It was painstakingly done from life and took almost a year to complete. Painting plein air, Sargent worked 10 minutes at a time to capture that last fleeting moment of light before night sets in.

In the portrait of Gautreau, Sargent has captured his subject in motion. “Madame X’s body appears to press forward, a sensation reinforced by slight projection of her dress’ bustier and by the flexed tendons in her neck. These tensed cords make us intensely aware of the supreme physical and mental effort that she must exert to hold her head in profile, while keeping her body in adamantly, even aggressively, frontal position” (Painted Skin, Sidlauskas). In reality, the twist that defines her pose could only be held for a couple minutes.

Similarly in Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, the flowers, the youthful nature of the girls, the lantern’s candlelight and the diming twilight all represent a fleeting moment. It is a beautiful image but it is also profoundly melancholy because everything that makes this image beautiful cannot last.

In those early Florentine portraits, the artist aimed to present the fundamental characteristics of the sitter. Painted without space, light or movement, the sitter is presented as fixed. These “paintings embody the universal, the eternal, rather than the specific and the transitory aspect of things” (The Florentine Profile Portrait in Quattrocento, Lipman). In this context beauty is also fixed.

In Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, the warm orange-pink glow of the candlelight that illuminates the girls’ lanterns is set against the cool purple atmosphere of crepuscule. The soul of this painting is this contrast of warm and cool light. Again the source of sublime in Sargent’s painting comes from labour not nature. The little girls are creating a sight of beauty by lighting their lanterns.

For Sargent beauty is not natural. Madame x is beautiful because of her pose. The little girls are beautiful because of the light effect they create with their lanterns. He is rejecting the classical definition of beauty as innate. Instead, he presents beauty as something artificial and therefore democratic.

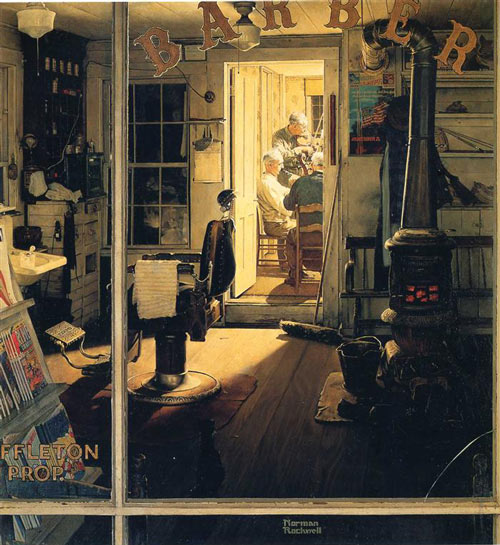

Throughout the 19th century, countries like France, the United States and Russia underwent revolutions which aimed to create more equal societies. During that period the realist art movement developed with the aim of making art more representative and democratic.

In his art, Sargent shares the role of artistic creator with his subject – a truly democratic act. Realism made fine art more representative by expanding the scope of subjects “worthy” of depiction. Sargent takes it a step further by transforming the role of the artist’s subject from passive object of admiration to creator. His work is a celebration of agency and the universal ability to create beauty.

Sources

Lipman, Jean. “The Florentine Profile Portrait in the Quattrocento.” The Art Bulletin 18, no. 1 (1936): 54-102. doi:10.2307/3045611.

Sidlauskas, Susan. “Painting Skin: John Singer Sargent’s “Madame X”.” American Art 15, no. 3 (2001): 9-33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3109402.

Khali Coulter, Debauched: Atypical Depictions of Female Agency and Gender Roles in Madame x. http://arthistory.us/display.php?eid=40

David Alan Brown, Virtue and Beauty. Virtue and Beauty: Leonardo’s Ginevra de’ Benci and Renaissance Portraits of Women. (2001) : pg. 11-24. National Gallery of Art Washington