I’m slowly pushing forward on an independent research project I started in the fall thanks to the curator Ric Kasini Kadour and the Rokeby Museum. My research is based on letters from a correspondence course in illustration (1891-1893) in which Ernest Knaufft of the Chautauqua Society of Fine Arts writes to his adolescent student Rachael Robinson Elmer.

As a trained academic artist, my contribution focuses on formal analysis of the drawing assignments and feedback. As part of my engagement, I am reenacting the main drawing assignment. I want to show how the course rejects the idea of drawing as a kind of image making and instead presents it as a form of research through observation. This idea of going beyond reproduction and striving for conceptual understanding is evidence of a philosophical rigor embedded in the illustrative tradition.

Drawing Course

Drawing practices are taught in this course through a series of assignments that can be broken down into three categories: copying old master drawings, drawing from life and drawing from imagination. Throughout the letter’s Knaufft meditates on the theoretical difference of copying and drawing from life. He develops an argument in which he claims that copying teaches the artist the craft of drawing (theories on mark making), while drawing from nature teaches the artist abstract concepts related to scientific theories on light, optics and geometry. The art advocate and illustrator Andrew Loomis calls the later the Form Principal.

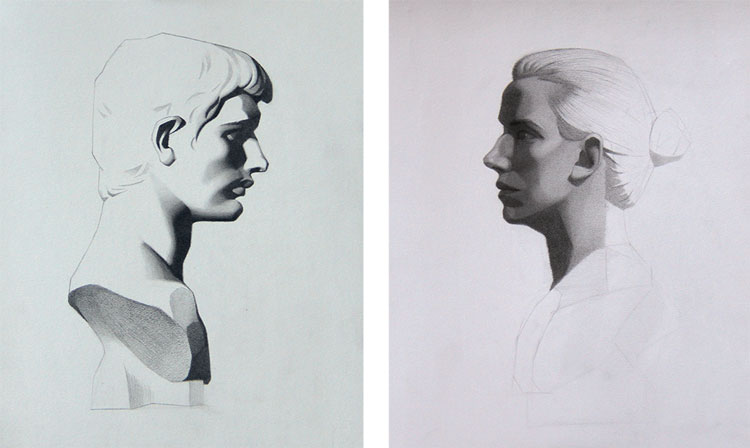

Throughout the course Knaufft assigns different old master drawings for his student to copy. Generally these drawings are from the French school and portrait images. As a follow up exercise Knaufft asks Elmer to recreate the subjects position and lighting, using herself as a model in front of the mirror.

He argues that true learning happens in this second drawing. That in trying to recreate the essence of an artist’s drawing from life, a young artist comes to understand the intention behind the effects in the master drawing.

In this way Knaufft makes an interesting theoretical distinction between craft and fine art. Craft is defined as an artist’s ability to learn a visual vocabulary used to replicate images. Fine Art is a search for knowledge through a process of observation that employs drawing as a kind of research tool.

Equal Access to Art Education

Also striking is the professional nature of Knaufft’s mentorship approach. This is illustrated by his detailed and direct criticism of Elmer’s assignments and his encouragement for her to apply to art publications.

In an article in the Art Amateur (an art magazine Knauft edited) Knauft outlines the requirements for a successful newspaper illustration career. In the article he states that a high level of art theory is not necessary for a successful career in the field. He explains that an illustrator can be successful with good ability to copy photographs (a process similar to copying old master drawings).

This suggests that the emphasis on drawing from life, in the illustration course, is not about preparing Elmer for a career as an illustrator but about providing her with full access to a fine art education.

The fact that this kind of higher education was being made available by correspondence – and to women – suggests the illustration tradition may have been engaged with socially conscious ideals.

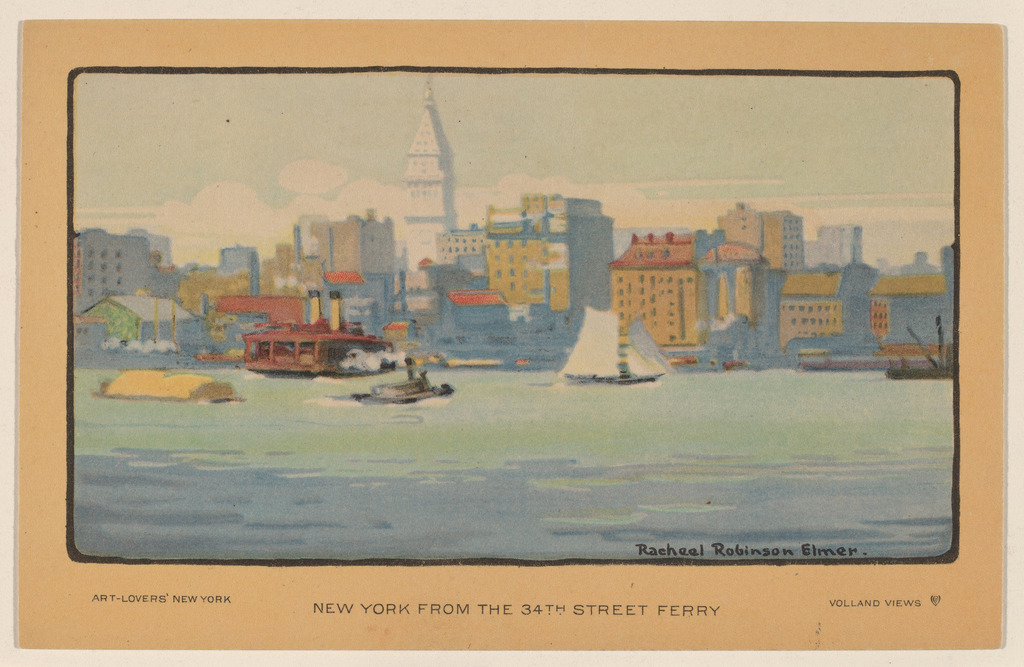

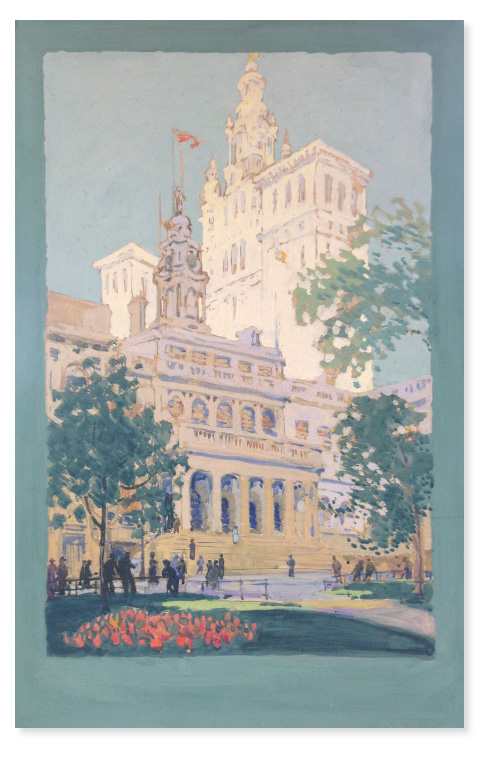

In Elmer’s case she went on to have a successful career as an illustrator. She is best remembered for a series of fine art postcards – prints from this series are part of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C..

While further research is required this hypothesis offer a new lens through which to understand the tradition.

Fingers crossed I’m applying for different opportunities to present my early findings and am working towards a creative project and eventual show.