Comparing the Avant-Garde and Naturalism

I came to Richard Thomson’s Art of the Actual looking to explore a theory. As a figurative artist, I’m fascinated by the 20th century rivalry between Modernism and classical realism.

I’m somewhat obsessed by Clement Greenberg’s manifesto, The Avant-Garde and Kitsch, because it reveals an important political link between the two schools central to his thesis. In his essay Greenberg defines the Avant-Garde as Modern art that emerges under Pablo Picasso and Kitsch as the art of communism developed under Ilya Repin.

In my rereading of his text I was struck by an idea. How would his argument change if we redefined Kitsch not as the art of the Russian Wanderers but that of the French Naturalists?

The Naturalists and the Wanderers are two 19th century artistic movements that have much in common. Both are offshoots of the French Academy and both were influenced by French impressionism and plein air painting. Moreover, both emerged during a time of social upheaval. The Wanderers emerged after the Emancipation Reforms of 1861 that effectively abolished serfdom throughout the Russian Empire. The Naturalists came to prominence under France’s Third Republic in the 1880’s which established a stable democratic republic. With this context both schools explore themes of equality, folk culture, and national fraternity.

What separates the two movements is the link between the Wanderers and communism and the Russian movement’s place outside of “Western Culture.” By thinking about Modernism in relation to the Naturalist movement we remove the element of “otherness” that Greenberg attached to the Kitsch (or realist) art.

A Book About the Naturalist Movement

Thomson’s book is based off a series of lectures he did as Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford University. Focusing on French art during the 1880’s and 1890’s, the book’s assertion is that Naturalism (not Post-Impressionism) was the dominant art of this period. He argues that the movement flourished because it suited the ideology of the Third Republic in its drive to establish a collective, modern and centralized France.

Although his focus is the Naturalist movement, Thomson gives much attention to early Modernists or Avant-Garde of this period known as the Post-Impressionists. He builds on his thesis of the central importance of Naturalism (in this period) by arguing that the Post-Impressionists of this period were very much in conversation with the dominant movement either as offshoots or critics.

Defining Naturalist Art

Thomson defines Naturalism as a kind of painting that sought to be clear, modern, descriptive and inclusive. Most of the Naturalist painters came from the French academic system, but distinguished themselves from the classical system by choosing to portray scenes of modern life. Their work celebrated anything from the labour of rural farmers to the latest advances in science.

Their choice and depiction of modern France was influenced by the state who sponsored the movement through commissions and concours for public art to decorate government buildings. In this way artists were not working directly for the state; however, given that the state was the largest purchaser of art at the time, artists did well to create art that would be met with approval by the government.

Avant-Garde Art

Throughout his exploration of the Avant-Garde, Thomson makes a compelling case that in many occasions the movement was actually aligned with the Naturalist aesthetic. He shows a plethora of works by Post-Impressionist artists which adhere to the conventions and subject of Naturalism. In so doing he suggests that the Post-Impressionism was not so much a radical break with the mainstream but a collection of divergent voices still within the culture.

Thomson explores how the Avant-Garde diverges from Naturalism over three chapters. He outlines how the Avant-Garde used caricature, popular culture and what he coins as “organicism” (ideas around flux) to disengage with the dominant movement.

I found his description of the Avant-Garde illuminating, but found myself wanting to group his argument differently. For me what seemed to surface again and again was the influence of “Café Théatre ” culture on Avant-Garde art.

Café Théatre’s Influence on Art

Café Théatres were dinner theatres specializing in popular culture. As Thomson explains, by the 1880s these establishments had been professionalised and were extremely profitable. They became so popular that artists from more “serious” theatre were performing in these venues.

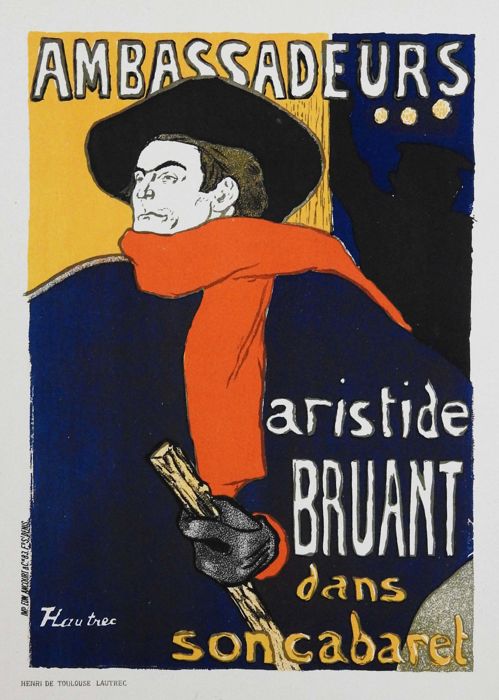

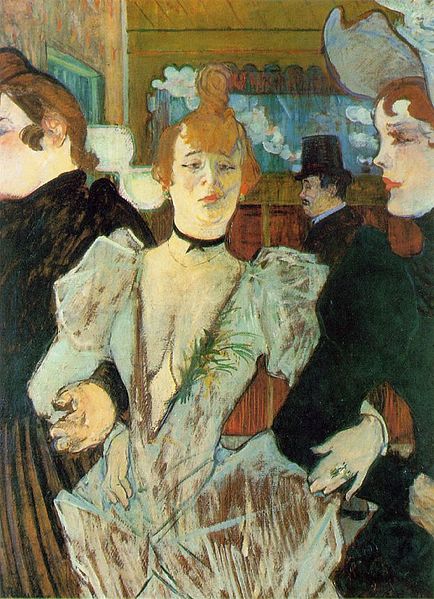

Avant-Garde art from this period uses the Café Théatre as its main subject. So much so that I remember being shocked the first time I saw the austere attire of a woman in a Henri Fantin-Latour painting. I realised, having grown up on Modern art, I had always kind of assumed that French women of the periode dressed in flamboyant colours with a generous décolleté. I’ve come to understand that the woman of a Toulouse-Lautrec painting is not your average French citizen but someone working in one of these Café Théatre.

Subject was not the only way in which the Avant-Garde was influenced by the Café Théatre. Beyond theatre, these venues contributed to visual culture through poster art (that is now considered fine art) and the publication of satirical revues which helped popularise caricature art.

Naturalism favoured exacting description over style. Unlike past movements like Rococo or Neo-Classicism, Naturalism did not have a distinctive style. Even in its time critics often lamented its photographic nature.

Thomson writes that one way the Avant-Garde could distance itself from Naturalism was through style. Although each artist strove to create a unique style, Thomson shows how the group took many ideas from caricature and popular culture of the time – which was part of the Café Théatre culture.

Adding my own interpretation to Thomson’s work, I would argue that their choice of stylistic influence was part of the Avant-Garde’s larger exploration of the Café Théatre culture.

Public vs. Private in Art

Interestingly, Café Théatres were a meeting place for both the proletariat and the bourgeois. A rare space in the society where the different social classes met on equal terms. These spaces embodied the values of the Republic, égalité, fraternité, liberté. While the Cafe Theatre does not challenge the state’s definition of itself, it shows a very different image of the culture.

Naturalism focused on the public or civic life of its citizens and showed a hopeful image of modern French culture: productive labour, technological progress and social progress. In contrast, the work by the Avant-Garde showed a kind of private life and depicts a more decadent scene: sex workers, drinking, and gambling.

For me, thinking about Naturalism and Modernism in terms of the Public and Private space is an important way to situate the two movements before embarking on the 20th century rivalry that would split the two movements. On a superficial level, Modernism seems to break with its predecessors on stylistic terms. I would argue that what really separates Modernism from previous generations is this shift in focus from public to private life.

Café Théatre was a space where every citizen (at least the male ones) could escape their social identity and ‘be themselves’.

Naturalist paintings reflect images that are representative of how the state wants civilians to look and what it wants them to see. Whereas Café Théatre is private not because people are in the shelter of their homes, but because they are acting in a way that gratifies their own desires – and not those of the state.

This represents a move away from arts traditional role of representing and speaking for the state (whether it be a democracy, a monarchy or theocracy).

Yet Thomson makes an important critique of this so called popular art. He notes that many of the artists adopting this popular style and subject matter were themselves from upper class society. So although the viewer is granted access to these socially open spaces, it is only from the vantage point of the upper class.

Russian Art compared to Naturalist Painting

Although the Wanderers and the Naturalists painted similar subjects, the work was conceptually very different.

Interestingly, the Wanderers were not supported by the state. In fact the group originally formed in protest of the state-sponsored academy, which they felt stifled artistic freedom. After the lifetime of the group, their art was adopted by the new communist government and their legacy was twisted to align with the values of the new ideology.

The group was supported by private collectors, mostly from the emerging industrial class. They sold their work through travelling exhibitions – hence their name.

Naturalism, aligned with state interests, worked to define a new archetype: the modern french citizen. Pastoral scenes of workers in the field were meant to highlight the idealised public contributions of every citizen working to build the third republic.

Especially in the beginning, the art of the Wanderers was less idealistic. Instead of presenting the working poor as a type, the Russian artists aimed for an authentic depiction of the individual life of their subject. The work celebrated the progressive change in the country but it could also be critical of the state, depicting the hardship of peasant life.

I would argue that 19th century Russian art, like early Modernism, was interested in the private concerns of the individual. Unlike the Modernists, several of the group’s members were from the same humble origins as their subjects.

For the Wanderers this effort to show the internal world of the sitter was about humanizing the subject. Like Alexandrovich Yaroshenko who invites the viewer into the internal universe of his subject in The Stoker as a way to arouse compassion for oppressed people.

I’m not sure that I see the same kind of compassion for the subject in the work of the French Avant-Garde.

Greenber’s Rejection of Russian Art

What frustrates me about the Greenberg essay is that it rejects Russian art without actually engaging with it.

In a footnote, added to Greenberg’s essay when it was reprinted as part of a book in 1961, the author notes that he misattributed a painting of a heroic war scene to Repin. He explains that only after printing the essay did he learn that Repin had never painted a battle scene. This error highlights the author’s lack of understanding of Russian art.

My aim is to point out that our original perception of art can be manipulated. The meaning of art is malleable depending on the context in which it is seen.

When we consider post-war art, it’s important to recognise the political alignment of different schools of art. In the same way that Naturalism and Social Realism were sponsored by the French and Russian state, Modernism was supported by the American government. When Norman Rockwell presented his Four Freedoms series to the American government he was initially turned down because it wasn’t in the Modern aesthetic. It makes sense, Modernism with its commitment to freedom of self expression suited the ideology of the American government – just like Naturalism aligned itself with France’s Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité.

My point isn’t to disparage the Avant-Garde. I think Thomson’s book does an excellent job of showing how Post-Impressionism was an important critical voice in the face of the hegemony of Naturalism.

Naturalism covered a vast array of subject matter in a highly detailed style. Seen in isolation, one would think it an encyclopedic portrait of France during the late 19th century. Post-Impressionism exposes the idealised nature of the work and challenges the communal vision it portrays. In turn the art of the Wanderers reveals the voyeuristic gaze of Modernism.

After reading Thomson and Greenberg, I’m left thinking about the importance of questioning the dominance of any one school of painting (or thought). No image can be a full account of truth. Looking at works of a similar subject across genre and culture is one way to expose bias and build an understanding of truth.

Sources:

Richard Thomson, Art of the Actual: Naturalism and Style in Early Third Republic France. (2012). Yale Books

Elizabeth Kridl Valkeiner, The Wanderers: Masters of Nineteenth-Century Russian Painting: An Exhibition from the Soviet Union. (1991). Dallas Museum of Art

Clement Greenber, Art and Culture: Critical Essays. Avant-Garde and Kitsch (1961) pg 1-33. Beacon Press Boston