The women of 19th century Grez-sur-Loing

There is something both compelling and moving, I felt, in the way certain male artists portrayed women: a kind of longing that was not just an expression of the erotic…[but] a desire to be the other as well as to view her, and at the same time an acknowledgement of irrevocable separation. – Wendy Lesser

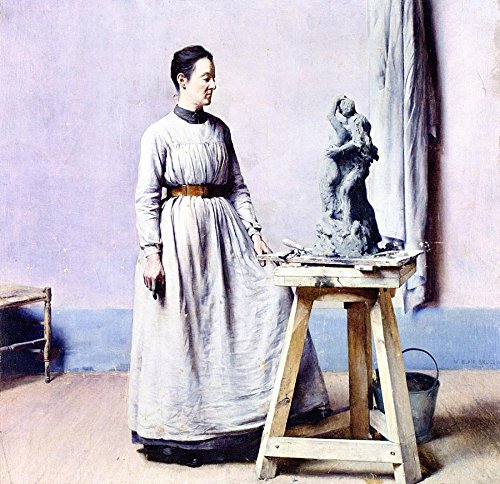

Femme Sculpteur is a portrait of the Swedish artist Caroline Bruce produced by her husband, the Canadian painter William Blair Bruce. The painting was exhibited at the 1891 Salon of the Société des Artistes Français in Paris, France.

The two met a decade earlier in the small artistic community of Grez, France. Like many small French villages at the time Grez was home to a community of artists painting landscape in the impressionist style.

What set Grez apart from many of the other artist colonies was its cosmopolitan nature (Swedish, British, American and even Japanese artists painted there) and the presence of a large contingent of female painters.

History remembers the men, but women actually had a commanding presence in 19th century impressionist painting – a fact currently being celebrated in the show, Her Paris: Women Artists in the Age of Impressionism, curated by Laurence Madeline.

R-E-S-P-E-C-T, find out what it means to me

To say this was a golden age for women’s liberation would be an exaggeration. Women only ever made up about 10% of exhibitors at the salon and, as Madeline talks about in the catalogue for her show, much of the work of these pioneering women has been lost overtime.

Interestingly, one record of the female artists in Grez that has survived is works by male artists depicting these women working in Grez. Paintings like the above Double Portrait, by Francis Chadwick, depict women at work and as professional equals to their male counterparts.

The sort of respect shown to the female subject is noteworthy if we consider how women were portrayed in the preceding Rococo and the eventual Modernist periods.

Social propriety in the 19th century

After a visit to the Bruce couple, the German artist Jelka Rosen had this to say about the work of our ‘Femme Sculpteur’ Caroline Bruce:

In her studio she had the life-size nude of the baker in Grez which she had done for the Salon. This nasty statue stood in her sitting room in a corner with its back to the public, so as not to show his sex, althou [sic] she had modeled this part in great detail.

Women at the time were under a great deal of pressure to follow strict moral codes. In the arts this presented a real challenge as the instruction of the day was based around the study of the nude model. Moreover, the idea of a women moving to an artist colony and living alone was also considered risky behaviour.

So how did so many women overcome this sort of societal pressure?

Reasonable accommodation for women

Mary Alcott Nieriker (sister of Louisa May Alcott) wrote a “how to guide” for women wishing to study art in France. In her book she encouraged women interested in plein air to choose Grez over the risky Barbizon which was known for its vie boheme.

Grez’s reputation as accommodating to “female needs” was due to the Hotel Chevillon and “Mère” Chevillon who acted as a sort of den mother to women staying in her lodging keeping the place “respectable” for female guests.

Many of the women at Grez came from the Académie Julian, a private art school in Paris which was the first French institution to accept women.

In the early years of the Académie women were simply “not excluded” and allowed to study alongside men. According to the school’s founder Rodolph Julian the women that joined the school were all foreigners. In an interview with Sketch, a British art journal, Julian comments on this arrangement:

It was extremely awkward and disagreeable and I soon saw that if I were to hope to get my own country women to work with me I should have to make different arrangements.

His solution was to set up a separate atelier for women. During a period of transition, women could choose to study in one atelier or the other, but eventually rules were established that excluded women from the men’s atelier.

It’s very easy to look at the situation through a contemporary lens and criticize the separation and supervision of these women.

However, Art Historian Catherine Fehrer suggests that in the case of the Académie this decision was not taken on account of male students but “responded more to the needs of bourgeois families who […] were fearful of mixed classes.”

This idea that the women’s ateliers were more of an accommodation than an assault on women’s rights seems credible when you consider that women’s enrollment at the Académie rose from a handful of students to 50 to 60 per year after the separate ateliers were established.

Women encouraged to compete

Another sign of the director’s commitment to his female students is the way in which internal concours (competitions) were organised.

The school was renowned not just for teaching its students technique, but also for teaching them how to survive the art world. Monthly concours were organised for students to learn how to prepare for the competitive Salon system that awaited them after their studies.

Although women and men studied in separate facilities, the competitions were mixed and adjudicating professors were not told the name or the gender of participants until after prizes were awarded.

Many women from the Académie did go on to show in the Salon. Rosa Bonheur, the foremost animal painter of the time said, “M. Julian understands that by determination and perseverance, a woman can very well equal a man in the science and the arts.”

This is by no means a story of revolution, it is a story of reform. It is an example of how a society can work to understand the needs of a marginalized population and find ways to begin including them.

In our present age where the question of equality is ever being negotiated, this story of the inclusion is a relevant example of how considerate accommodation can act as a catalyst for social change.

Sources used for this post:

Nochlin, Linda. (1971). Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? Woman in Sexist Society: Studies in Power and Powerlessness

Fehrer, Catherine. (1994). Women at the Academie Julian in Paris. The Burlington Magazine (Vol. 136, No. 110), pp. 752-757

Curator, Bruce, Tobi ; with essays by Gehmacher, Arlene & Koval, Anne & Gredts, William H. & Fox, Ross. (2014). Into the light : the paintings of William Blair Bruce (1859-1906)

Edited and Introduced by Murray, Joan. Letters Home: 1859-1906 The Letters Of William Blair Bruce. Newcastle: Penumbra Press , 1982. Print